A comet with a narrow tail in the evening twilight, with uncertain but potentially high brightness ?

General comments on simulations: The simulations in this page are aimed to provide reasonable expectations in terms of tail length and shape. They can help anticipate how a comet apparition will unfold, when the highlight of the display should happen, and what the comet appearance should be. This is a useful tool for preparing to a comet apparition. Yet, due to the unpredictable future activity of the comet and the habit of comets to defy predictions, one should not think these simulations will perfectly forecast the exact shape and extend of the tails of the comets.

The magnitudes displayed on the simulations are derived from the usual, simple formula, which tend to overestimate the brightness of Kreutz comets very close to perihelion (comet activity does not change on very short timescales, and as dust is very quickly destroyed near Sun, the comet is not as bright as the simple formula predicts).

For Kreutz comets, the pre-perihelion tail is overestimated in the simulations, as Kreutz comets generally appear more gaseous and less dusty before perihelion, whereas after perihelion they are 100% dusty (as simulated) with little to no gas emission.

SUMMARY

Comet C/2026 A1 MAPS is a sungrazing comet belonging to the Kreutz family, which includes several historically famous objects such as comet Ikeya–Seki and the great comets of 1843 and 1882. More recently, smaller members of this family have appeared, including C/2011 W3 (Lovejoy) and C/2024 S1 (ATLAS). Comet MAPS was discovered much farther from the Sun than these recent comets, at a heliocentric distance of about 2 AU, whereas Lovejoy and C/2024 S1 ATLAS were detected at roughly 0.8 AU. This larger discovery distance suggests that comet MAPS could be significantly larger than those objects.

Because of their extremely small perihelion distances, Kreutz comets are subjected to intense heating, thermal stress, and tidal forces, which frequently lead to fragmentation. As a result, it is not possible to predict for sure if comet MAPS will survive perihelion or not. Still, a reasonable level of confidence can be obtained by considering the comet’s size, which can be estimated from its pre-perihelion brightness. However, given the well-known tendency of comets to defy expectations, no outcome should be considered guaranteed.

What we will see when the comet gets out of the twilight depends almost only on the level of activity of the comet after perihelion, specifically on the amount of dust emitted between ~6h to 3-4 days after perihelion. Smaller Kreutz comets (such as C/2024 S1 ATLAS) typically break up before perihelion and leave nothing to be seen. Larger comets (such as Lovejoy) may fragment after perihelion, producing “headless comets”. If the nucleus is large enough, the comet can survive perihelion intact and appear as a fully developed comet, as did Ikeya–Seki and the great comets of 1843 and 1882.

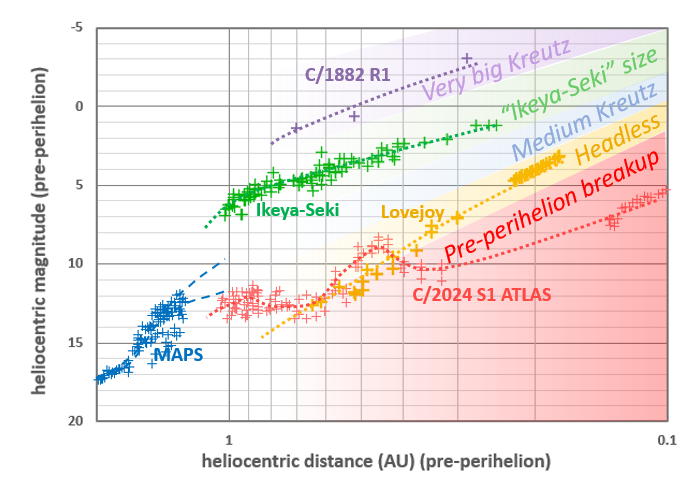

To assess which outcome is most likely, I made a plot showing the pre-perihelion heliocentric magnitude (which correlates with nucleus size) of comet MAPS and various Kreutz comets as a function of heliocentric distance. The plot highlights several possible scenarios depending on comet size.

- Small Kreutz comets (e.g. C/2024 S1 ATLAS) that break up before perihelion

- Comets similar to C/2011 W3 Lovejoy that fragment after perihelion and appear as headless comets

- Medium-sized Kreutz comets

- Large Kreutz comets such as Ikeya–Seki

- Very large Kreutz comets such as C/1882 R1

MAPS appears to have entered its “switch-on” phase around February 4, with a rapid increase in brightness. This phase is usual for periodic comets that have previously experienced the intense solar heating during past perihelions. A brightening of several magnitudes over a short timescale (a few weeks at most) is expected. Once the brightness stabilizes, it should be possible to better constrain the size of MAPS relative to other Kreutz comets.

Currently (February 26), the comet’s brightness is still increasing, though the rate of brightening appears to be slowing, suggesting the “switch-on” phase is terminated. Comet MAPS could turn out to be a “medium Kreutz”, intermediate between Headless comets and “Ikeya-Seki” size. This corresponds to the “Scenario 3” of my simulations. At this stage, simulations should only be considered as “reasonnable expectations”. Nothing will be certain until a few days after perihelion, as it is the dust released between ~6 hours and 3–4 days after perihelion that mostly determines the tail’s length and brightness.

the different scenarios, going from pre-perihelion breakup to “Ikeya-Seki” size comet are simulated for comet MAPS below.

In all cases, the most favorable observing latitudes are near the equator and southward, roughly between 20° N and 45° S. For Kreutz comets with perihelion occurring in spring, Earth lies close to the comet’s orbital plane. As a result, the tail appears very narrow and straight. This geometry increases the tail’s surface brightness, significantly enhancing its visibility. This viewing geometry is similar to that of the 1843 comet, which appeared in March and display a bright, long and narrow tail. However, MAPS will be about 25% farther from Earth, reducing both its brightness and potential tail length compared to 1843 comet.

In all cases, the comet emerges from twilight around April 7. Over the following days as the comet gets farther from the sun, the tail length increases while the tail’s surface brightness decreases. Moonlight will begin to interfere around April 22, after the peak display of comet MAPS has likely concluded.

Scenario 1: Pre-perihelion breakup

This scenario corresponds to a small Kreutz comet that breaks apart shortly before perihelion, similar to comet ISON. Even with substantial dust release at breakup, most material would be destroyed at perihelion. Only a faint remnant might emerge afterward, detectable by space-based coronagraphs such as LASCO C3 or CCOR, but likely too faint for ground-based observation.

As of February 12, this scenario appears unlikely, as MAPS seems significantly larger than objects that typically follow this path.

Scenario 2: Headless comet (post-perihelion breakup)

This scenario corresponds to a Kreutz comet similar to or slightly larger than C/2011 W3 Lovejoy, which fragments shortly after perihelion. Dust released during breakup forms a prominent tail, while the nucleus itself disappears, producing a headless comet such as Lovejoy or 1887 B1, the “Headless Wonder.”

I simulated this case using the same outburst and dust-emission profile as Lovejoy. MAPS might retain a small head when it emerges from twilight on April 7, but would likely become fully headless within a few days. The optimal viewing window would then be April 9–11, when the tail could extend beyond 15°. Afterward, the tail would fade rapidly, although narrow-tail geometry could allow photographic detection for longer than was possible for Lovejoy.

if the current brightness trend of the “switch-on” phase lasts long enough, it seems probable that comet MAPS might exceed the size implied by this scenario.

Scenario 3: Medium-sized Kreutz comet

In this scenario, the comet survives perihelion. It could be photographed near perihelion in broad daylight using telescopes and cameras, though it would remain a challenging naked-eye object except under exceptional conditions.

Near perihelion, an unusual effect may occur: as the comet accelerates toward the Sun and executes its perihelion turn, the comet’s head would separate from the tail, as dust emitted at perihelion is rapidly destroyed, while older dust emitted earlier remains farther from the Sun and survives. As the comet recedes after perihelion, a new tail forms, potentially appearing alongside remnants of the pre-perihelion tail. This unusual configuration could be visible in space-based coronagraph images.

The comet would emerge from solar glare around April 7 with a tail length of approximately 5°–10°, increasing to about 20° by April 13, while its overall brightness gradually declines. In this scenario, although the tail is bright “from an astronomer point of view”, it remains probably not bright enough to reach a wide impact on the general public.

Scenario 4: Ikeya–Seki–sized Kreutz comet

In this case, the comet is even larger and survives perihelion with very high activity. It would be extremely bright near perihelion and potentially visible to the naked eye in daylight close to the Sun. Coronagraph images could show both inbound and newly formed outbound tails simultaneously.

Upon emerging from solar glare around April 7, the comet would display a bright tail of roughly 10°, growing to approximately 30° by April 16, while fading in brightness. Because Earth lies near the orbital plane, the tail’s surface brightness could exceed that of Ikeya–Seki. However, this same geometry would produce a very narrow, featureless tail, lacking the beautiful twists and internal structures observed in Ikeya-Seki. In this scenario, the high brightness of the tail would probably make comet MAPS reach the general public.

Will comet MAPS become a “Great Comet”?

I think it is a real possibility, but only if the comet is a “Ikeya-Seki” size comet, which is far from granted. Although comet MAPS would not display an expansive, fan-like tail like comet McNaught, the higher surface brightness of a narrow tail could make it easier for the general public to observe. Combined with a highlight period lasting one week, which is longer than the brief peak of comets like McNaught or West, comet MAPS could achieve wide visibility and public impact for those located in the right range of latitudes.