- C/1680 V1 Kirch

Comet Kirch was the greatest comet of the 17th century. It was a rare “non-Kreutz” sungrazer comet, with a perihelion distance even smaller than the Kreutz family. On top of it, the geometric circumstances were very good for Earth. The comet passed perihelion behind the sun and then was hurled by the Sun in the direction of the Earth, with a minimum Earth distance of 0.5AU (notably closer than all of the main Kreutz sungrazers), and perfect position for northern hemisphere. All of this contributed to make comet Kirch one of the best sungrazer comet in recorded history, with an extremely bright tail reaching 90° at the end of year 1680. In order to be able to simulate the correct tail length, I had to use a n=5 slope parameter to have sufficient dust production near sun. With the standard n=4 slope parameter, the tail reached no more than 60° length. The simulation show the extraordinary growth speed of the tail: a few degrees on December 19th, 40° on 22nd, 60° on 25th, and 90° on 28th. Then the decrease of tail length also matches the observations, with 50° on January 8th and 40° on January 15th. The only notable discrepancy is the tail length reported by Pontio of 70° on December 22nd.

- C/1577 V1, Great comet of 1577

Among the 50+ comets that i have simulated, the great comet of 1577 stands out as possibly “the greatest of the great”. The comet had an almost perfect combination of parameters. First, the great comet of 1577 was an intrinsically big comet with zero-ish absolute magnitude. Second, it came close to the sun, with a short perihelion distance of 0.18AU which is ideal for generating an extended dust tail. Third, it had relatively favorable geometric circumstances, with a post-perihelion apparition, and even though the closest approach to Earth was still at a relatively large 0.63AU distance, the extended dust tail got much closer to our planet. The geometric circumstances also provided significant forward scattering boost (about 1.5 magnitude during the best part of the appearance), and made the comet getting out of the sun glare rather quickly. And lastly, the best part of the apparition was mostly without any moon interference.

From the reports, coming essentially from the northern hemisphere, the comet is considered one of the greatest comets, initially shining as brightly as Venus, with a spectacular tail. Yet, the simulation shows that it must have been an even more dramatic sight from the southern hemisphere, with a magnitude brighter than -6, and a huge, bright and strongly striated dust tail. Unfortunately, there is not any detailed report coming from the southern hemisphere, the only southern hemisphere report is from Peru and only tells the comet was visible through clouds like the moon.

According to the simulation, the highlight of the apparition must have been mostly limited to the southern hemisphere, happening between November 2nd when the very bright ~20° tail emerged from the sun glare, and November 12th, when the tail, though much longer (about 70°) and wider (it occupied a very large area of the sky), had already lost most of its luster. Yet, the tail was still much brighter than the one of any regular comet. From the northern hemisphere, the highlight of the apparition was between November 10th when the comet started to get out of the sun glare, and November 17th, when the moon began to interfere with the view.

- C/1471 Y1 Great comet of 1472

The comet of 1472 was a rather large comet that approached the Earth at a very close distance of 0.07AU on January 22nd. A single tail is mentioned in the reports. The tail length evolution mentioned as well as the rather large 4° width of the tail reported by Cato match the dust tail of the comet. A gas tail should have been longer all along the apparition of the comet, and should have been narrower.

The simulation renders well the growth of the tail, from around 5° in the beginning of January, to about 30° around January 20th matching very well the reports. After that date, the full moon began to interfere with the view and the tail was reported to shorten. However, the simulations shows that the tail must have kept growing, reaching a maximum length about 70° on January 24th, two days after closest approach to Earth. So it seems that the best part of the comet appearance was totally spoiled due to the full moon, and that, without moon, the comet would have been even more impressive.

At the time of close approach, the comet must have reached a quite negative magnitude probably around -3. It was reported to have been spotted in daylight in China. Some authors have raised doubts about this as the comet would have been very near Earth and thus quite large. I personnaly find this report very plausible, because contrary to all other daylight comets which appear very close the sun, the comet of 1472 was located at more than 90° elongation and near the north pole of the sky. Thus it did not need to the spotted in daylight in the sun glare, as it was visible during the whole night and could just be “tracked” during the day, especially as it was rather fixed in the sky. For comparison, Sirius can be seen to the naked eye in daylight, thus I find it very plausible that it could have been possible to track the comet during the whole day around the time of close approach.

Around the end of the month, it was possible again to observe the comet without moon but then the tail was shortening quickly. According to the simulation, the tail was about 30° on January 29th, and about 15° on February 3rd.

The only questionnable thing I find about this comet is its reported discovery in Europe around Christmas 1471, when it should have been magnitude 4 at the time of the full moon, which seems very improbable to me. Unusually, the Korean and Chinese reports came after these reports, in the beginning of January, so I suspect these early European reports could have been invented to give the comet a religious portent.

- C/1402 D1 (1402 apparition of C/1743 X1)

The great comet of 1402 has been identified by Meyer and Kronk as being the previous return of comet C/1743 X1 (Klinkenberg-Chéseaux). Indeed, while the previous official orbit from Hind was not a good match at all with the observations, the match between simulation and observations is excellent with Meyer and Kronk’s orbit. Similarly as during the 1744 apparition, the comet displayed striations visible in the morning in the northern hemisphere while the comet head was not visible. The only notable difference between simulation and reports I see is that, with perihelion date on March 25th calculated, the striation/multiple tails would probably show up best in the morning between 31st of March and 3rd of April, while they were reported on 26th and 27th of March.

From the southern hemisphere, the comet was probably an exceptional sight with the geometry of this apparition, with a very large rayed tail, initially very curved, then getting straight and very long, visible for a long time and at relatively large solar elongation.

- C/1264 N1, Great comet of 1264

The Great Comet of 1264 is considered one of the most remarkable comets in history. It was first observed on the evening of July 17, 1264, prior to solar conjunction. When it reappeared in the morning sky, observers reported that it had five tails, stretching up to 100° across the sky, resembling the fingers of a hand. As Earth crossed the comet’s orbital plane, the tails appeared to merge into one. The comet remained visible for over two months, displaying extremely long tails for an extended period. Such a prolonged display is characteristic of prograde comets with low orbital inclinations, which tend to stay relatively close to Earth for long durations. This behavior is the opposite of retrograde comets like Halley’s, which passes Earth with a high relative velocity, showing dramatic tails but only for a few days during favorable apparitions (e.g., in 1066 and 1910).

The “official” Hoek’s orbit places the comet’s perihelion distance at 0.82 AU. According to this orbit, the comet should have been bright and prominent in the evening sky well before its discovery, likely as early as late June or early July, when it was already shining at magnitude 2 and sporting a 10° dust tail. However, simulations based on Hoek’s orbit suggest the comet would not have displayed the kind of strong striations needed to produce the striking “finger-like” appearance described by early observers. As noted by Valz, the orbit of this comet is poorly constrained. All the comet positions used for the orbit determination come from after the solar conjunction, meaning only the outbound leg of its orbit is fitted by the orbit. Many different orbital solutions with varying inbound trajectories can still produce similar outbound paths. These alternate orbits can have significantly smaller perihelion distances and still fit the observed post-conjunction positions well.

To illustrate this, I computed an alternative orbit that matches the comet’s position from Hoek’s solution on August 20, but with a smaller perihelion distance of 0.27 AU. This alternate orbit results in a lower solar elongation prior to discovery and follows a similar path through the sky. Its parameters are as follows: eccentricity = 1.0, perihelion distance = 0.265 AU, time of perihelion = JD 2182929.45, inclination = 32.4°, longitude of ascending node = 166.8°, and argument of perihelion = 78.8°. With this orbit, the comet approaches stealthily from behind the Sun at low elongation. Its discovery on July 17 corresponds with the period when its brightness would have increased rapidly and its tail began to unfold. After solar conjunction, the comet would then exhibit strong striations consistent with the “finger” descriptions. Later, as Earth crossed the orbital plane, these striations would merge into a single, prominent tail.

While this orbit is only illustrative and not definitive, it demonstrates that orbits with lower perihelion distances can have positions after solar conjunction that are similar to the ones of Hoek’s orbit, while also offering a better match to the comet’s discovery timing and distinctive tail features. I may eventually develop a tool to compute alternate orbits for historical comets for which positional data are not accurate, by applying additional constraints, such as requiring low elongation prior to discovery, or using positional data with unknown date, to find orbits that might be more realistic than the official ones.

- X/1106 C1 Great Comet of 1106: see the page dedicated to simulations of Kreutz comets

- 1P Halley, 1066

On AD 1066, Halley comet made a spectacular apparition, a bit similar to the 1910 apparition, with tail length reaching more than 90°, but unlike 1910, there was no moon interference in 1066. The highlight of the apparition must have been between the 23rd and 26th of October, when the comet appeared in the evening just after solar conjunction. During this time, the dust tail must have appeared as a spectacular fan in the sky and the comet must have displayed a notable anti-tail like in 1910. Indeed, it seems the anti-tail was observed as there are references of the comet having 3 tails, like in the History of Normans: “a comet appeared which with three long extended rays illuminated a very great part of the south”

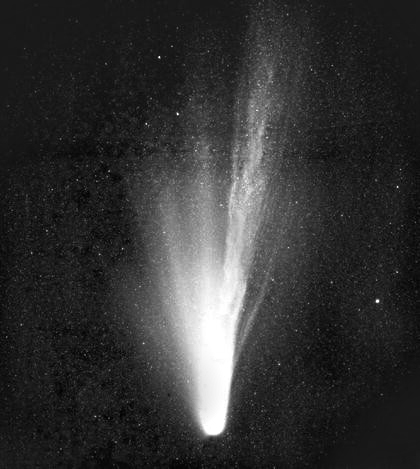

During the few evenings when the dust tail fan was spread over a large angle, it must have allowed an excellent view of the possible striations. Indeed, there are various mentions of the comet having multiple tails. An accurate report is the one of Sigebert of Brabant: “Over the island of Britain was seen a star of a wonderful bigness, to the train of which hung a fiery sword not unlike a dragon’s tail; and out of the dragon’s mouth issued two vast rays, whereof one reached as far as France, and the other, divided into seven lesser rays, stretched away towards Ireland.” The seven lesser rays were probably striation of the dust tail, a bit like on this image of Halley comet captured in 1986 when the dust tail angle was also spread enough to allow for visibility of striation, like in the image below.

- C/905 K1 Great Comet of 905

A great comet was visible in year 905. I simulated it using Hasegawa orbit. This comet was discovered around May 18th by various civilizations around the globe. According to the simulations using this orbit, the comet should have been discovered around May 4th or 5th, and have been an extremely great object in the morning sky with more than 20°, bright tail as early as May 7th, with tail growing to around 50° on May 12th. Furthermore, the moon was not interfering with the view at that time, and such an object being missed looks very odd. Thus it seems that the orbit of the comet might be wrong, and that the comet must have had a much lower elongation before discovery to prevent it from being visible.

- 1P Halley, 837

Comet 1P Halley made its closest Earth approach in 837 AD. It appeared in March, and moved little accros the sky for the whole month as it approach almost straight toward Earth. Its tails steadily increased in length, from less than 10° mid March, more than 30° at the end of the month, and more than 60° around April 8th. Then the closest approach made the geometry change very quickly, going to an unusual geometry as the comet got behind the Earth, and was seen almost “face on” at the time of closest approch on April 10th. This “face on” geometry made the comet appear smaller than a few days ago, and with unusual “curved” appearance, but great brightness, and in the middle of the night ! A the time of closest approach, the comet tails were no more 30° long. As the comet recedes from Earth, the tail got longer again and took back a more regular “straight” appearance, reaching more than 80° between April 12th and 15th. Then the tail length and comet brightnesss decreased very quickly at the same time as the moon began to interfere with the view.

- -372/-371 BC comet, Aristotle’s comet: see the page dedicated to simulations of Kreutz comets